What my Venezuelan team is saying about Maduro’s arrest

It wasn’t always like this between the U.S. and Venezuela

Hey there,

Happy New Year, and thank you for continuing to read The Weekly Shortlist in 2026.

We had a real break at Lupa over the holidays. Hiring slows down in late December and early January, and most of our team is in Latin America, where year-end breaks are taken seriously. I gave everyone two weeks of PTO before Christmas, and we came back online this week. I still took a few calls at the end because I am bad at fully switching off, but overall it was a good reset.

Coming back on Monday, the news about the U.S. attacks in Venezuela hit hard. The first thing I did was call Venezuelan colleagues and friends to check on their families and hear what they had to say. Then friends across the Americas started reaching out to ask what I made of it. When you live and work here, you get used to the gap between what the media shows and what people on the ground are actually experiencing.

The reality is complicated. Leadership in both countries is questionable. There are serious issues around international law, justice, corruption, and U.S. power. None of that disappears just because a president is toppled. But setting that aside for a moment, from a human and operator perspective, this is ultimately a positive development.

I started Lupa after spending years working across Latin America and meeting Venezuelans everywhere I went. I wanted them on my team. They are elite professionals. Resilient, adaptable, calm under pressure, and deeply aware that opportunities are not guaranteed. That last part matters more than most people realize. They do not get these opportunities back home, and it shapes how they work.

Years later, some of the Venezuelans on our founding team are still with me. I have wanted to visit Venezuela for a long time, something that has not been realistic for years. I still do not know when that will be possible. But I know what it would mean.

This week, we are talking about Venezuela, not as a headline, but as a country full of people whose talent has been constrained for a long time, and what it means when those constraints begin to shift.

Let’s get into it.

🌐 News Shortlist

1. What actually happened in Venezuela over the weekend

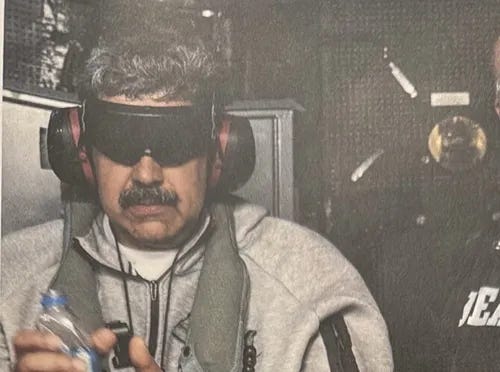

Recap: Early on January 3, U.S. forces launched military strikes on Venezuelan military sites and infrastructure near Caracas. Soon after, special operations forces captured Nicolás Maduro at his home. The operation took under two hours and met almost no resistance. Maduro was then taken out of Venezuela and brought to the United States, where he faces federal charges that were first made public in 2020.

The operation started at about 2 a.m. local time. The first strikes hit military bases, air defense systems, and supply sites to stop the Venezuelan military from organizing a response. Soon after, some areas of Caracas lost power and commercial flights were interrupted. U.S. officials said these actions were meant to prevent threats, not to retaliate.

After the strikes, U.S. special operations forces went into Caracas and headed straight to Maduro’s home. Reports say Venezuelan security forces did not put up much resistance. Maduro was arrested, taken to a U.S. aircraft carrier, and then flown to the United States. Within hours, videos and photos showed him arriving in New York and appearing in federal court.

The U.S. government described the operation as part of its ongoing fight against drugs and terrorism. Officials referred to long-standing claims that Maduro and top officials in his government are tied to drug trafficking and terrorist groups. These accusations had been around for years but had not led to direct action against Maduro until now.

In Venezuela, reactions were mixed. Maduro’s supporters called the operation a kidnapping and an illegal foreign attack. Loyalist groups quickly set up an interim leadership, while opposition leaders showed relief but also worry about the lack of a clear plan for what comes next.

International reaction was divided. Several governments in Latin America condemned the action as a violation of sovereignty. Others, particularly on the political right, expressed support or avoided direct criticism. European governments issued cautious statements focused on stability and human rights. The United Nations reiterated concerns about the precedent such an operation sets under international law.

In the United States, the operation triggered legal and political scrutiny. Questions were raised about war powers, congressional authorization, and the legality of capturing a sitting head of state without international approval. The administration defended its actions by citing post-9/11 authorities and national security exceptions, signaling that it views this as a continuation of existing enforcement policy rather than a new military conflict.

Right now, the biggest question is who will govern Venezuela. U.S. officials say they will run a transition. Sanctions, diplomatic ties, and economic policies have not changed, so Venezuela remains in political limbo even after Maduro’s removal

2. A brief history of relations between the U.S. and Venezuela

Recap: Throughout most of the 20th century, the United States and Venezuela had strong political and economic connections. Venezuela supplied oil to the U.S. reliably, and American companies were active in the Venezuelan energy sector. Trade between the two countries grew steadily. These close ties lasted until the late 1990s, only starting to weaken after Hugo Chávez became president in 1999.

Things were different in the past. For many years, Venezuela was one of the closest partners in Latin America. U.S. oil companies helped build up Venezuela’s energy industry, especially after big oil discoveries in the early 1900s. By the middle of the century, Venezuela was one of the world’s top oil exporters and a major supplier to the U.S., especially during World War II and the years that followed.

The connection between the two countries went beyond oil. Compared to its neighbors, Venezuela was considered politically stable and kept its democratic institutions for much of the late 1900s. American companies invested in many areas, and Venezuelan professionals, engineers, and executives often moved between Caracas, Houston, New York, and Miami. In the U.S., Venezuelans were seen as skilled workers and business partners, not as refugees or political exiles.

Things started to change in the late 1990s. When Hugo Chávez was elected in 1998, he took a more confrontational stance toward the U.S. and made the oil industry more political. Even though trade and oil exports to the U.S. continued at first, trust faded as the government took greater control and the country’s systems weakened. The relationship did not end all at once, but slowly fell apart after almost a hundred years of close ties.

When considering Venezuela today, it’s important to remember that cooperation, not conflict, was the norm for most of its history. The decline in U.S.–Venezuela relations happened only recently. If the two countries rebuild their relationship in the future, it will probably look more like a return to their old economic ties than something completely new.

3. What reopening Venezuela could actually mean for U.S. business

Recap: Now that Nicolás Maduro is out and a transition period seems to have started, people are beginning to focus on what’s next for Venezuela’s economy and its ties with the United States. Sanctions are still in place, the government’s future is uncertain, and no one knows how long this will last. Meanwhile, Venezuelans both at home and abroad are openly talking about the chance to rebuild economic connections, find work, and team up with U.S. companies.

I want to be thoughtful about this. I don’t want to come across as opportunistic or as the gringo who assumes Latin America is just waiting to be discovered. That stereotype exists for a reason. But when I talk to Venezuelans, including my colleagues, I don’t hear resentment. I hear anticipation. Many are truly excited about the chance to work with Americans again, as equals, without politics getting in the way.

This is important because business ties between the U.S. and Venezuela didn’t fall apart due to a lack of compatibility. They broke down because the institutions failed. The talent was always there. Venezuelan professionals adapted, moved abroad, and succeeded elsewhere. Now there’s a whole generation that knows global standards, remote work, U.S. business culture, and how quickly opportunities can change. That mix is hard to find.

Since this is a business newsletter, let’s talk about timing. Many U.S. companies already work with Venezuelans remotely, and that’s become normal. The real question is what will happen when working together in person is possible again. It won’t happen overnight, and there are risks, but it will happen eventually. Offices, partnerships, and a long-term presence will only succeed for companies that take time to understand the country before everyone else rushes in.

Advice:

If you run a company with exposure to Latin America, start learning now, quietly and seriously. Build relationships, not narratives. Work with Venezuelan talent where they are today, and listen to how they think about the future. First-mover advantage does not come from being early to extract value. It comes from being early to understand how to build something that lasts.

That’s it for this week.

I know this was not a standard edition of The Weekly Shortlist. But this is not a normal moment, and pretending otherwise wouldn’t be honest. Venezuela is not just a headline or a policy debate. It’s people I work with, people I trust, and people whose careers were shaped by forces far outside their control.

If there’s one thread running through everything here, it’s this: talent doesn’t disappear when a country breaks. It moves. And when conditions change, even slowly, that talent looks for ways to reconnect, not to settle scores.

If you’re a founder, operator, or hiring manager interested in Latin America, now is the time to listen more than you speak. Get to know the history. Have real conversations. Focus on building relationships before making plans.

If you’d like to discuss what this might mean for your team or hiring plans, feel free to reach out. My calendar is always open.

Until next time,

Joseph Burns

CEO & Founder, Lupa